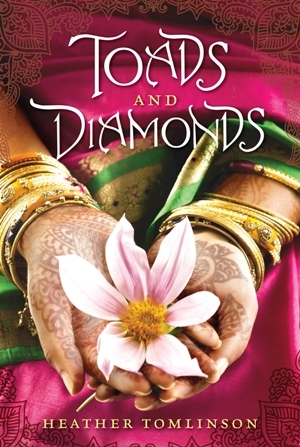

The library had Toads and Diamonds temptingly displayed on the YA shelf, reminding me I’d been planning to read it for three years now. I remember looking at the blogosphere reviews in 2010 and thinking it was *exactly* my thing. It’s a reworked fairy-tale (Perrault’s “The Fairies”)–a species of storytelling I’ve loved ever since I read the first Datlow & Windling anthology back when I was barely out of the egg. Moreover, Toads… is set in a world resembling the Indian subcontinent, and features two strong PoC heroines. And I’d liked Tomlinson’s earlier novel Swan Maiden very much. So I checked out the book right then.

Stepsisters Diribani and Tana work hard to eke a modest living after their father, a gem trader, was killed by bandits. Diribani is beautiful and gentle, while Tana is plain-spoken and practical–and each has the other’s back. Life is difficult–not only are they suddenly poor, but their land has been colonised by the white-coated Believers, who scorn the natives, calling them dirt-eaters. The Believers venerate the One God, and require women to veil their faces, while the native religion (that Tana and Diribani observe) involves the worship of a dozen gods, has girls wearing their dowry on their person in the form of gold bangles, and abhors the consumption of meat. Although Tomlinson is deliberately reticent with many specifics (for instance, the girls are said to wear “dress wraps”), those familiar with Indian history will recognize the Mughal empire in 16th century-ish India. And while Tomlinson is careful with the details, she wisely does not make the accuracy of the setting a pillar of the book– Toads and Diamonds is driven by plot and by its strong characterizations.

When Diribani helps the goddess Naghali over at the sacred well, she’s granted a boon– precious stones and flowers drop from her lips when she speaks. Then Tana in turn meets the goddess, but spews forth snakes and toads instead. This is a really interesting development, for Tana wasn’t rude to Naghali–rather, the goddess grants each devotee the gift she deems fitting, one that’ll fulfill their innermost desires. Moreover, snakes are respected in this culture–not only are they viewed as emissaries of the goddess, but are valued for the practical purpose of pest control (each house has its own rat-muncher snake). I really enjoyed the way Tomlison calmly subverts the snakes/toads= ick trope in this book. Frogs are lucky! People worship snakes! Everyone wants a nice muscular ratter for their home like I want a Little Free Library for mine! The only downside to Tana’s gift is that some of the snake slithering forth from her mouth are venomous. Oh, and that the Governor of their province hates the practise of snake worship, and has ordered their mass slaughter.

Diribani plans to use her riches to build hospitals and animal shelters and libraries and to hold art workshops (I love this utopian socialist-y Mughal kingdom, I do), but her step-mother advises caution–the greedy and all-out nasty Governor Alwar will undoubtedly exploit Diribani’s gift for his wicked ends once he hears about her powers. What are the sisters to do with their gifts? Fate intervenes when the handsome Prince Zahid, younger son of the Emperor, gets accidentally involved in the fix. He decrees that Diribani will spend her time as the guest of the crown, with the ladies of the royal court at the city, while Tana will live near the sacred well so her snakes may be released in the wild. Governor Alwar would love to kill Tana and cloister Diribani, but he can only nod and smile when the Prince issues his command. But he isn’t finished yet, oh no.

Diribani now embarks upon the long journey to the city with the Believers, learning more about their culture and in turn teaching them about hers, and hanging out with Zahid. (Tomlison deals with the religious aspects very gracefully–no simplistic dismissal of veiling or dowry bangles here–and we come to understand both sides better through Diribani’s eyes). Meanwhile Tana, unwilling to stay meekly in her secluded home, sets off on a pilgrimage to seek wisdom. The two girls grow and learn and understand the true value of their gifts. And there’s a lovely ending that pulls it all together without resorting to any standard happily-ever-after devices.

Once the girls go their separate ways, Diribani’s story is much quieter than Tana’s. I felt Diribani’s storyline could use a bit more jump, and that Tana’s could have slowed down. Diribani’s journey is relatively uneventful, dealing with her gradual understanding (and widening appreciation) of the Believers , and hence is packed with description and inner monologue. By contrast, Tana rapidly goes through a series of hardships (she shovels cowdung, drags a handcart full of corpses, falls very ill etc. ), and is constantly on the move, so much so that I had trouble keeping track of her movements. Although Tomlison paces her work carefully, alternating chapters for Diribani and Tana, the arrangement didn’t quite work for me–I think I’d rather have had more continuity in the read for Tana’s storyline. That said, these are very minor issues in a deftly-written, tightly-woven novel. Recommended for the setting, the telling, and for featuring a goddess with a fine sense of humour. Read it!