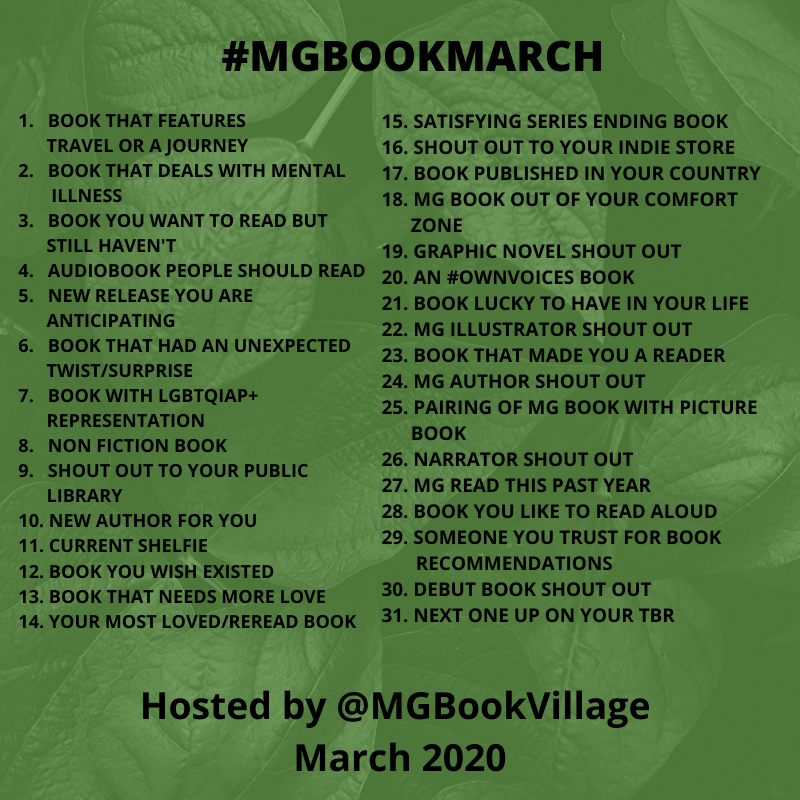

It’s been a busy winter, but now I have time to blog about books again! I’ve joined MG Book Village’s middle grade book celebration this month. Every day in March, I’m going to post here and on twitter about a MG book that fits the day’s category. Please join in the fun!

Day 1 (March 1) Books that feature travel or a journey: The Night Diary by Veera Hiranandani, featuring a young refugee girl’s journey from Pakistan to India in 1947.

2. Deals with mental illness: The Weight of Our Sky by Hanna Alkaf. Set in Malaysia, featuring a teen protagonist with OCD.

3. Want to read but still haven’t: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith. What can I say?

4. Audiobook people should read: So…I’ve never ever heard an audiobook. But the obvious answer is a graphic novel, I’d think?

5. New release you are anticipating: Since I didn’t answer yesterday’s question, I’ll over-compensate now. I can’t wait for Three Keys, Kelly Yang’s sequel to the wonderful Front Desk. I’m also keen to read Quintessence by Jess Redman. And I’m totally waiting for Aru Shah and the Tree of Wishes by Roshani Chokshi.

6. Book that had an unexpected twist: The Bridge Home by Padma Venkatraman. Everything about this book gave me the feels, but the twist at the end was simply outstanding.

7. LGBTQIAP representation: The Parker Inheritance by Varian Johnson. Such a clear-eyed, unflinching look at racism and homophobia and systemic inequality. TPI is about family, adventure, courage, and the hopefulness of being young. It’s also a great page-turner!

8. Non-fiction Book: The Boy who Harnessed the Wind by William Kamkwamba. Lovely story of a boy from Malawi who hacks a windmill to provide electricity to his village.

9. Shout out to your library: I love California’s public library system. My county lets us request books from all over the Bay Area, for free!

10. New Author for you: I discovered Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor last year, and have re-read it twice already. It’s become one of my go-to comfort reads.

11. Current Shelfie: It’s all ebooks right now. No library visits with our lockdown!

12. Book you wish existed: This one has me stumped. We live in a rich MGlit world right now!

13. Book that needs more love: The Grand Plan to Fix Everything by Uma Krishnaswami. An Indian American girl from Maryland moves to small-town India, where she meets her favorite Bollywood star. Such a gentle, funny, wise book!

14. Your most reread/loved book: An impossible challenge, to pick just one! But…I’m going with Calvin and Hobbes. Endless joy with every reread.

15. Satisfying series ending book: I love The Other Wind, the last book of The Earthsea series by the incomparable Ursula Le Guin.

16. Shoutout to your indie store: I love Pegasus Books and Moe’s Books, both in Berkeley.

17. Book published in your country: A very ambiguous tag for those of us who have multiple country affiliations. I’ll go with the place I grew up, and pick Malgudi Days by R.K.Narayan.

18. Book out of your comfort zone: I’m picking a novel that’s a prose poem: Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai. Splendid, triumphant, edgy story of a young Vietnamese refugee girls’s struggle to adapt to Alabama.

***

I’ll add to this post daily. Please participate if you are on Twitter and help readers discover great new MG books! Don’t forget to post your recommendations with the tag ##MGBookMarch